4EVER - Luca Federico Ferrero

4EVER

Text by Saverio Verini

“To remember what we will never forget”*

Luca Federico Ferrero at Société Interludio

I still remember the first time I tried to decipher that strange word made up of a number and a series of letters: 4EVER. I knew a little maths, but I didn’t know English; for this reason, the writing engraved on the desk that I had inherited from someone who had attended the fifth grade in that same classroom – the year before or who knows when – was indecipherable to me. I had to resort to the wisdom of a friend of mine who was clearly more experienced in the ways of life: ‘it is pronounced “forever”, it means “per sempre”.’ The two proper names that preceded the ‘4EVER’, joined by a ‘+’, announced a promise of eternity, a formula as simple as it was perfect. I don’t remember what those names were; even the author of the writing, as well as the date it was made, remain unknown.

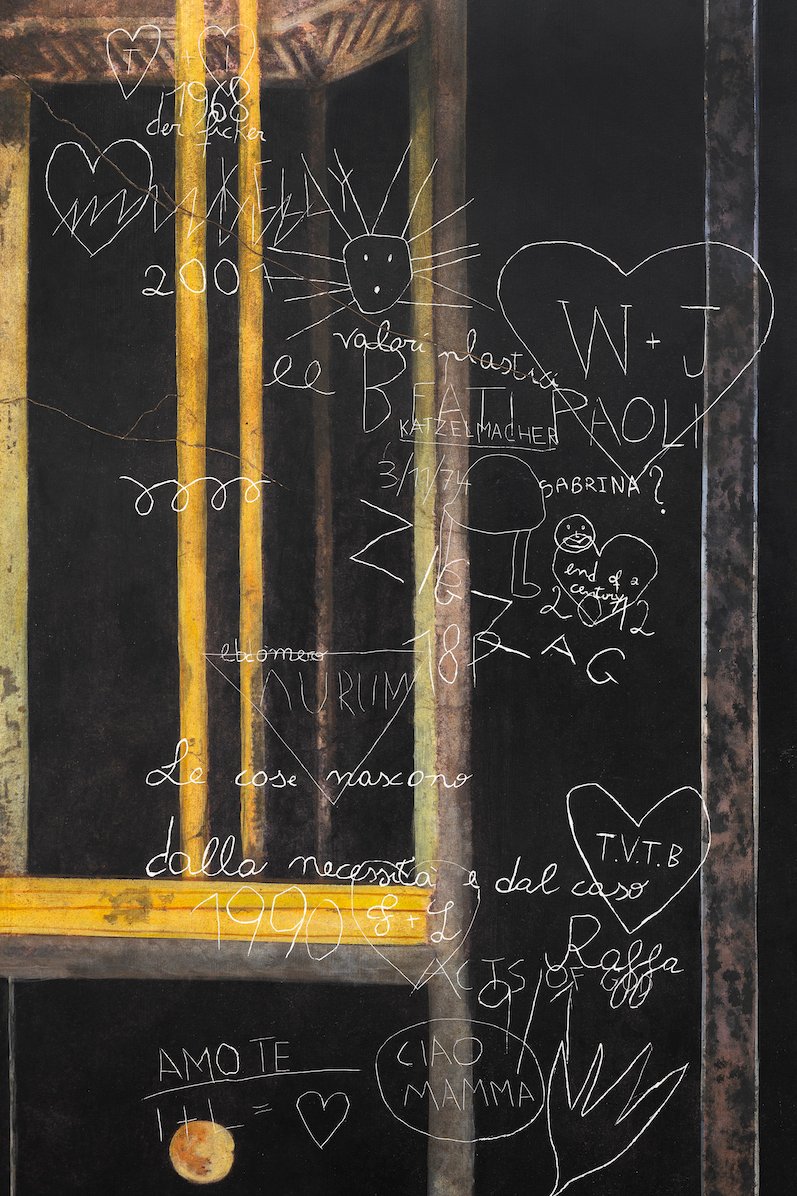

I can’t help but think of this little episode – a childhood encounter with the eternal struggle between the duration of things and their inevitable impermanence – when faced with the works of Luca Federico Ferrero. The series, presented at the exhibition by Société Interludio, raises a wide range of considerations: on the passage of time, on the status of the work of art, on authorship. But let’s proceed in order. The works show signs of clear vandalism. Scars furrow the surface of the wall paintings – mostly Pompeian-style frescoes – compromising their appearance: the same kind of writing that sometimes makes the news in August, with the odd tourist caught leaving their mark at an archaeological site. A slight shiver runs through me as I observe these scratched, defaced surfaces. How can anyone want to mark such ancient splendour in this way? However, it is a calculated act of tampering. The paintings are indeed detached frescoes, but they were painted recently; and the signs that scar them were produced at the behest of the artist himself.

The idea stems from an everyday observation, that of the many beauties marred by an atavistic instinct, by man’s desire to leave a trace, to be there. The same instinct that probably led each of us to carve our initials on the school desk, the name of a loved one, a line from a song, an insult. Ferrero has decided to subtly subvert this irrepressible impulse and the instinctive content it generates. In addition to hearts and marks that simulate those left by a middle school student on a school trip, the writings that give voice to these walls are in fact cultured quotations: ‘Things are born of necessity and chance’, a phrase embroidered by Alighiero Boetti on a tapestry; the famous 19th century motto “épater les bourgeois”; a drawing by Enrico Baj; a scribble taken from the painting Fallimento, by Giacomo Balla; the “truism” – ’never write bullshit’ – that Alighiero Boetti added in pen to a poster by Jenny Holzer, then gifted to Maurizio Cattelan during a meeting at the Venice Biennale in 1990. And here we have our first paradox: the ungainly and self-referential writing is elevated to a message of wisdom, even erudition. A wisdom that evidently, in Ferrero’s ideal world, should travel on walls and even overlap with the art of the past. I like to imagine the various authors who, like teens grappling with their first group outings, meet up to engrave their maxims on these surfaces.

All the frescos, as we were saying, are dotted with these and many other references, like notes – reminders – that Ferrero wants to share with the rest of the world, in the same way that a lover carves the name of their beloved on the first available surface, and it matters little whether or not it is artistic heritage. On the contrary, the older the medium, the better. Those who perform the defacement, often in the name of something they believe in wholeheartedly, want to compete with the past, aspiring to the same durability, the same resistance to the passage of time. The inscription wants to cling to the monument like a tattoo to the skin. Ferrero seems to be driven by a similar desire, which he has decided to sublimate through a crossover between eras, with the simulation of different temporalities re-proposed in the here and now. This is the second paradox of the series on display. Ferrero invests us by projecting a double nostalgia onto the works (and onto us): on the one hand that of the dated fresco, of the archaeological site, of classicism, of the mural painting found in some medieval abbey; on the other hand that of vintage vandalism, a vandalism with a Seventies-like taste to it, I would dare to say almost a sweet one, which brings to mind the uncertain calligraphy of times gone by, school trips and naive teenage bravado. It’s as if history with a capital H collided with a more human-scale history, imperfect and crooked, in an battle for attention that is unequal and, perhaps for this very reason, awkwardly tender.

Ferrero seems to believe in this challenge between distant temporalities, to the point of reversing the writing, ennobling it, not through the calligraphy – that remains rather basic and brutal – but thanks to the meaning of the sentences and drawings. Then again, it is not the first time that ‘doodles’ have been recognised as having creative potential, if not a real artistic status. The shepherd Giotto surprised by the master Cimabue while giving vent to his graphic impulse by freely drawing on stones and other ‘natural’ surfaces is an example of this; as is the exaltation of automatic and spontaneous handwriting and signs, expression of an art free from conditioning. Many artists and intellectuals between the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century saw the possibility of a ‘regeneration of art’ in children’s drawings and scribbles, with the avant-gardes ready to welcome the vital impulse of child-like creation, to unlearn and find a new origin. An example is the series that the photographer Brassaï, who was close to the surrealists, created in the 1930s, ‘portraying’ the graffiti on the walls of a Paris that was anything but the Ville Lumière.

Ferrero employs qualified workers in the process of creating his works. The detached frescoes are reproduced using a technique that is extremely faithful to the original (to the point of being able to deceive us). While maintaining his authorship well-defined, the artist adopts the strategy of sharing and delegating the creative act, a path that has been followed – in different forms – by some of Ferrero’s idols (Boetti, Cattelan…). By proposing a type of painting that is not practised and by inventing pasts that interact with each other, Ferrero shows that he belongs to a profoundly conceptual line of Italian art, in which I seem to descry some noble filiations, more or less conscious: the reference to the layered temporalities of Flavio Favelli, the sense of humour of Piero Golia, Vedovamazzei and Paola Pivi, the wild power of the written word (even when presented in the form of a quotation) of Marcello Maloberti’s Martellate.

Ferrero seems to me to hold these matrices together in a completely personal way, focusing on the ability of his works – not only those exhibited in Société Interludio’s venues – to arouse both attraction and repulsion, to be full of grace and at the same time strident, controlled and visceral. The 4EVER series is a rather emblematic demonstration of this, with the many thoughts that it manages to stir and condense. It is generally a good sign when, in the space of a few inches, a work of art is able to be so eloquent.