DESIDERIO. Atto Secondo

DESIDERIO

ATTO SECONDO

Critic text by Giulia de Giorgi

Movement underlies all becoming.

(Paul Klee, Creative Confession, 1920)

DESIDERIO – ATTO SECONDO tells of a lack that keeps renewing itself, of a quest that has no destination. The time of completion is not now, but is constantly postponed. The space of fulfilment is not here, but elsewhere. It is desire as an inexhaustible source that comes from its own depths and drives the individual to wander in search of what he has not yet encountered, in an attempt to suspend the flow of time.

Piove anche sul mare (It rains also on the sea), observes Nazzarena Poli Maramotti, with positive resignation, in a surrender to the inevitability of phenomena that we cannot control. When it rains on the sea as well, there is nothing left to do but let the rain enter and to be crossed by the flood. When the drops of the sky merge with the drops of the sea, water is reunited with itself. Above and below become one, references are lost, along with the perception of one’s own body and its relationship to its surroundings. How to recover it, to find the centre again?

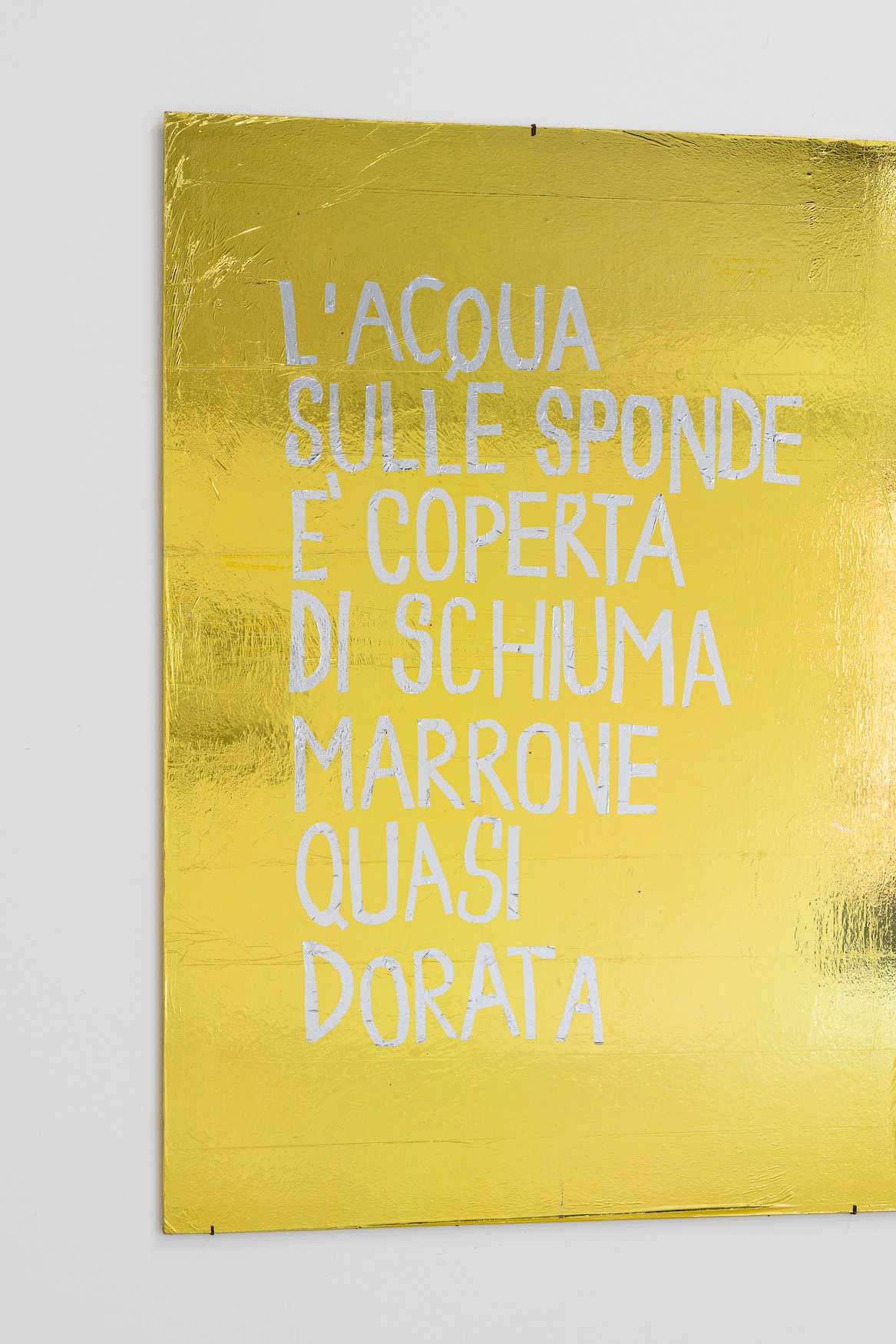

With the drawing of a rudder and an anchor, Eva Marisaldi seems to offer useful tools for orientation in this difficult navigation by sight, to steer and moor the boat. Actually, she throws us into the present, taking us out of a timeless dimension and into the history of events. Shimmering gold, a symbol of preciousness, here screams tragedy. “The water on the shore is covered with brown, almost golden foam”: apparently neutral words – alluding to a change in the environment – written on an emergency thermal blanket, to manifest the analogy of two unnatural situations that we cannot accept. Facing them we, Osservatori di onde (The wave watchers), feel our existence as part of a collective existence.

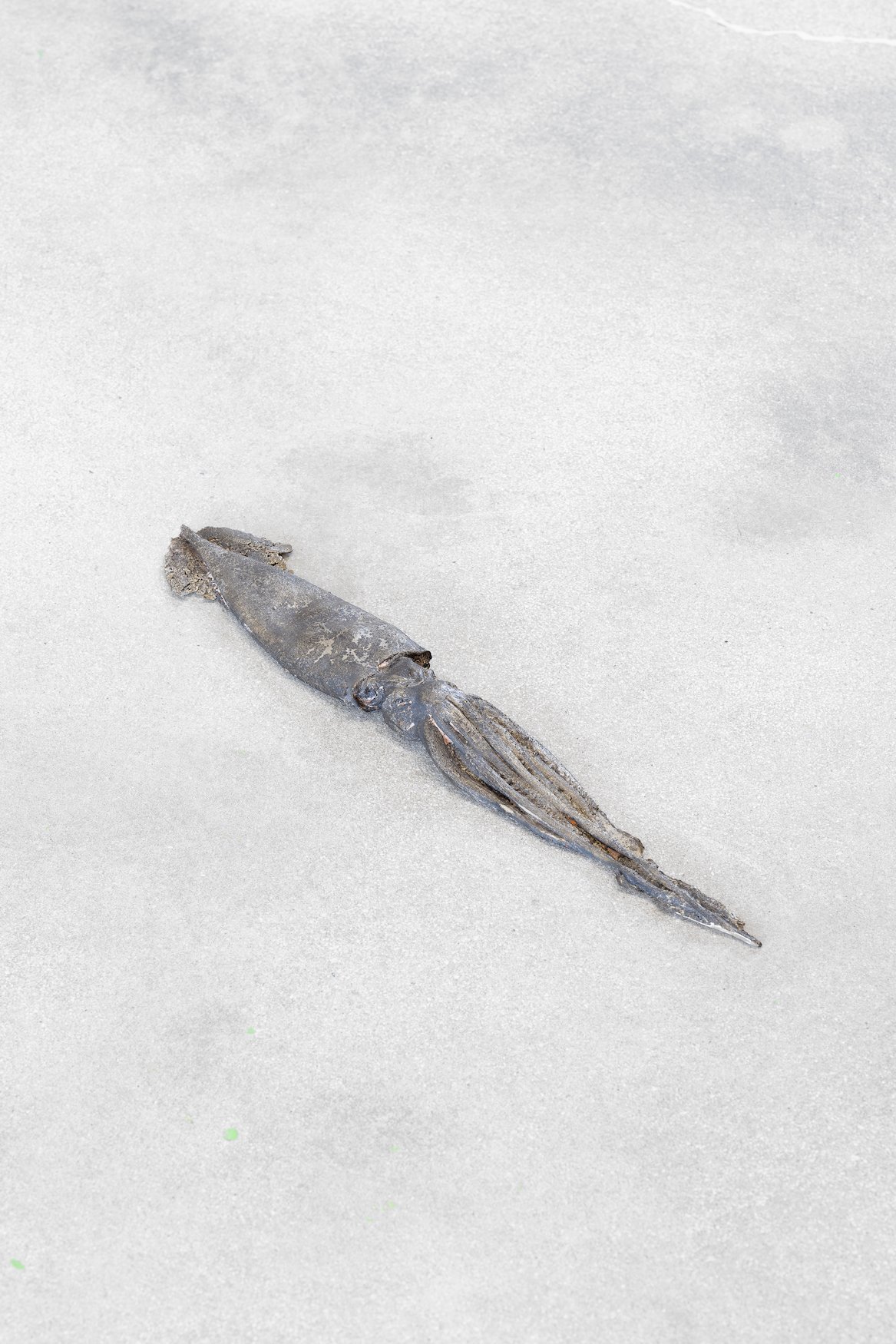

A state of calm accompanies the re-appropriation of previously lost references. Andrea Barzaghi paints the moment Dopo la tempesta (After the storm), when the individual reacquires his centre again, emerges from a seemingly endless whirlwind and regains his own identity. At this point, he recognizes not only himself but also the other-than-self. He discovers – or perhaps remembers – that he was not alone during the flood. Two human bodies move now, by choice or necessity, in opposite directions, just like Gianni Caravaggio’s two sea creatures: Un polpo e un calamaro si allontanano tra di loro per incontrarsi dall’altra parte del globo (An octopus and a squid move away from each other to meet on the other side of the globe), linked by an invisible thread.In their movement and the inevitable change of condition that accompanies it, the octopus and the squid make us feel temporality – moment by moment – and spatiality – metre by metre. Who knows, at the end of their journey, meeting at a point we cannot know, the two creatures may decide to begin their journey again, reversing their direction. They could, thus, suspend time forever, escaping the transience to which all things of the world are subject, in order to exist in a potentially infinite moment.

The short-circuit that Luca Federico Ferrero creates in the 4ever series disrupts the linear sequence of chronological events. In one section of the fresco, the author of the Pompeian painting and that of the contemporary graffito meet – or clash – at the two ends of a line connecting past and present. In between, stands a third author, to whom Ferrero delegates the material realisation of the fresco. What is the work at this point? The co- presence of temporal planes would suggest all of them, but at the same time none: each specificity is left out in order to be included in a larger story.

In Mark Handforth’s work, the passage of time becomes visible in the melting of candle wax. In its plasticity, the light of the flame becomes a tangible manifestation of the energy released by combustion. As the candle is consumed, the shell undergoes a less perceptible and certainly slower evolution: both are subject to a transformative process, revealing the inevitability of change, whether latent or apparent.

An emblematic image of transformation and cyclical movement is the wave, which wets the sand and recedes, leaving the shore different from before each time. Ruth Proctor fixes the image of a section of the ocean onto a sheet of paper, coated with chemicals and impressed by sunlight. The sheet of paper records the process over a specific period of time. The artist, immersed in the water in an attempt to capture a transience that cannot be reproduced, is as one with the natural element, inseparable from the wave that is taking shape in that moment: the water, leaving its imprint, becomes a vehicle of knowledge.

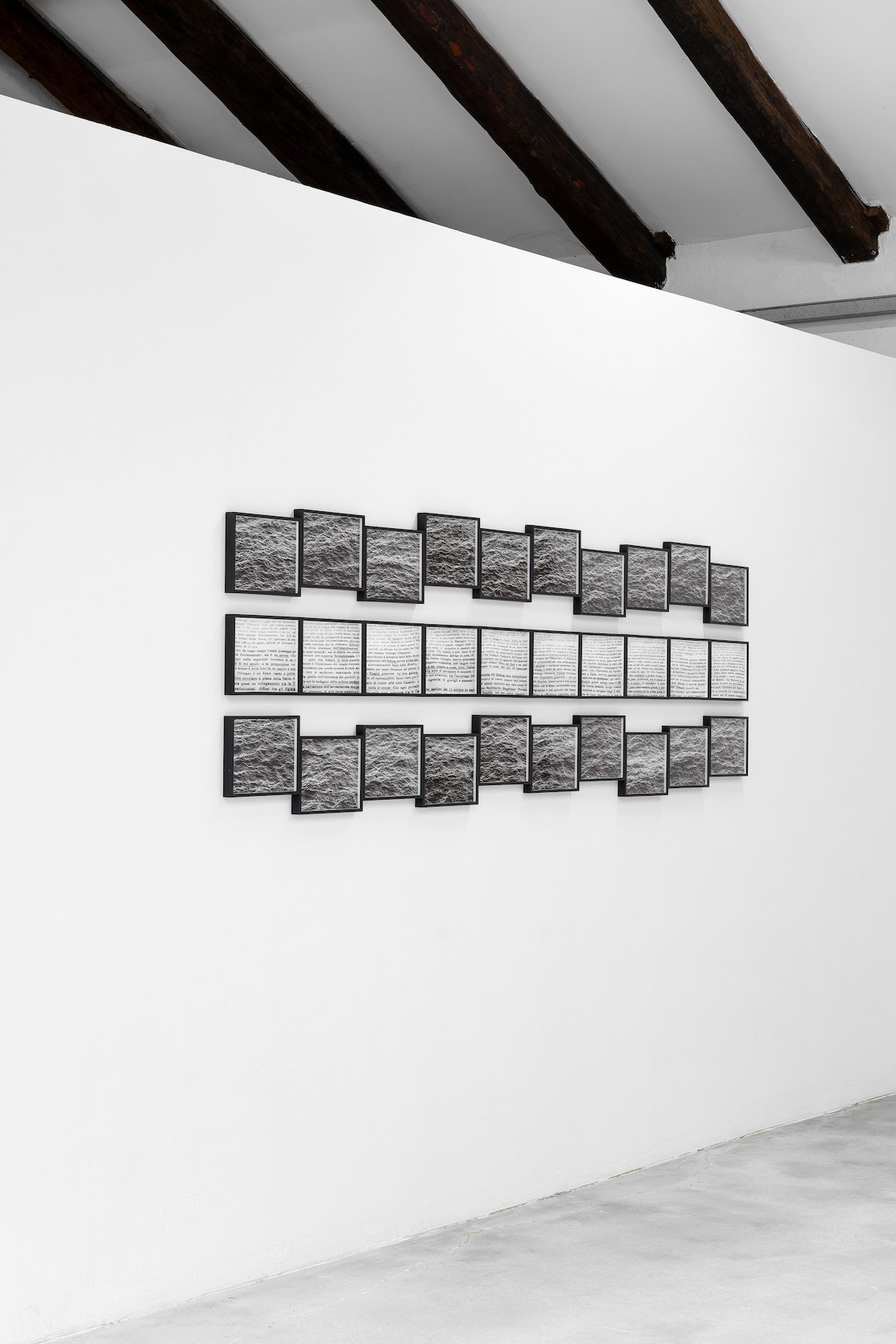

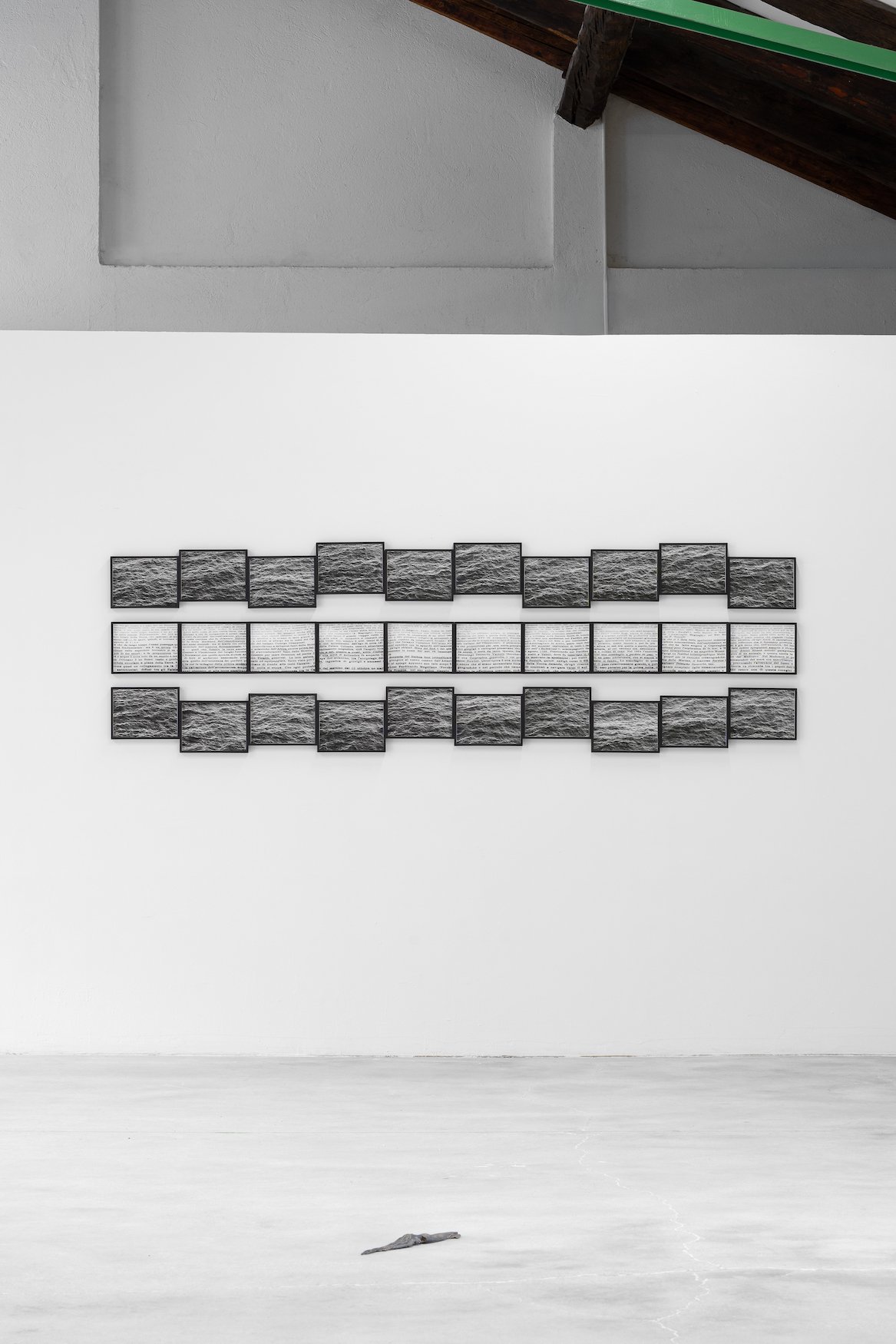

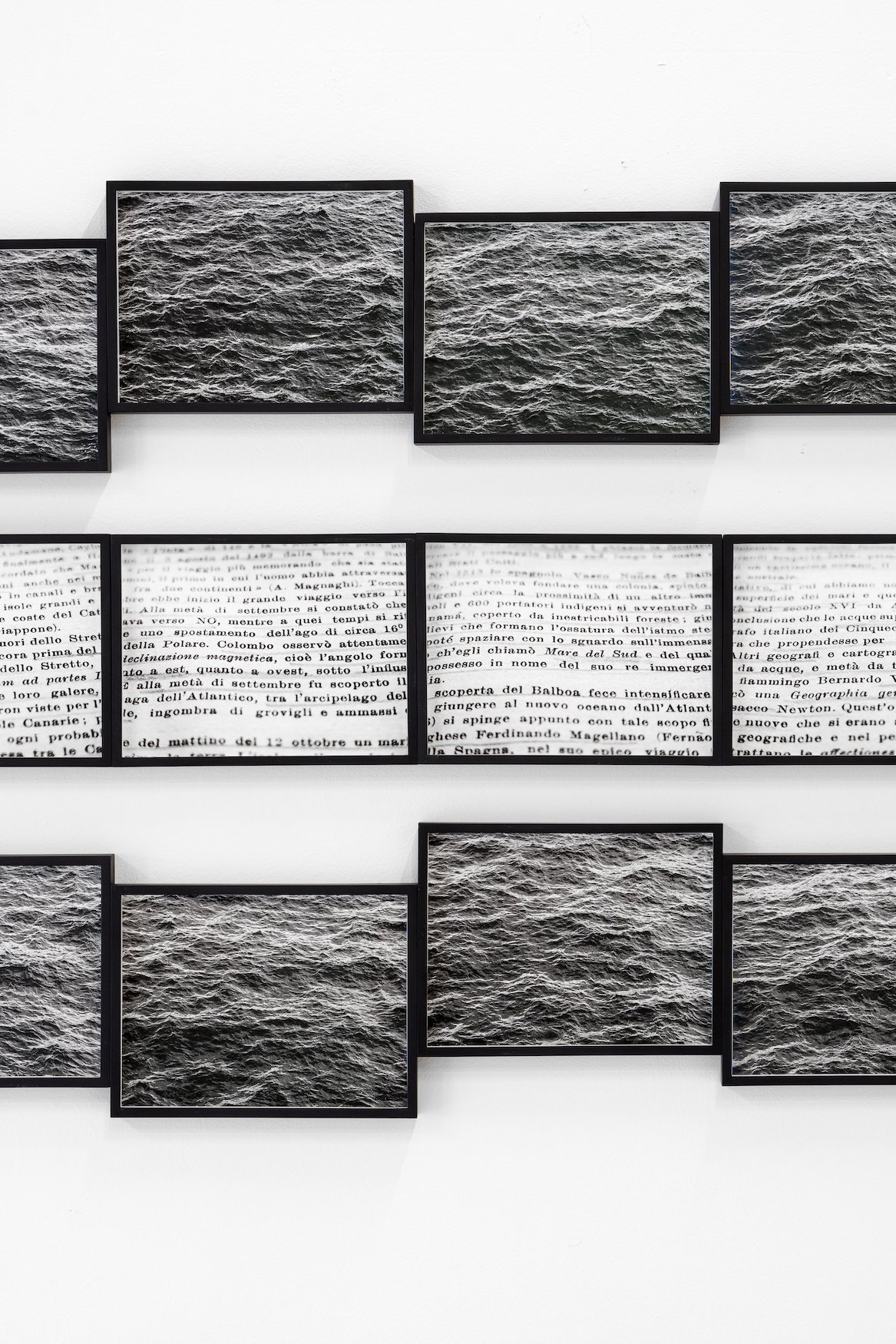

Water reflects the movements of the soul, which can be read like pages in a book: Joachim Schmid combines photographs of the sea surface with details from a text. Verbal description goes hand in hand with visual depiction and the process of thought. The inner reality is not revealed, but takes the implicit form of a crossing of an ocean of words, in which we recognise ourselves as rational beings, standing above a flow that in Francesco Gennari’s drawings instead emerges and manifests itself spontaneously. Here, the alternation between ‘drawn writing’ and erasures has the rhythm of water breaking on the shore. The two gestures are equivalent, they are both painterly gestures.

One cannot exist without the other, within a lump of signs that measure the artist’s subconscious. The trace on paper, almost a graphite impulse, mimics the unconscious flow with an apparently random language that settles in order to then erode, in a continuous coming and going. “To write with the left hand is to draw,” Alighiero Boetti said.

In Eugenia Vanni’s work the spontaneous matrix is made up of everyday objects: kitchen boards invaded by ink, filling in the cuts left by the blades that have furrowed their surface over the years. Through the different and random levels of engraving, the resulting printed image bears witness to everyday life and the memory of the family context. The title of the work, Sturm und Drang, plays with the domestic dimension and the use of the common object, here elevated to an epic dimension in reference to the Romantic movement.

If in Eugenia Vanni’s work the layers of memory are brought to life, in Francesco Carone’s Tempesta these layers are deliberately covered, concealed. The work, entrusted each time to a different artist – who works on the same support, creating a new image, albeit inspired by the previous one – changes on the surface, preserving the dynamic of creation and destruction underneath. Constantly renewed, the work is always the same and always different, like the author, at the mercy of precariousness and disorientation in the face of nature. The painting, destined to an end only with the death of the artist, lives in a process that caresses circularity and repetition, affirming to then obliterate. The author, in the impossibility of remaining the same, forgets himself, only to find himself again in a constant change.